Symbol Declarations

Symbol declarations occur in modules and are delimited by the symbol  . The most important symbols are constants and theory inclusions (which are special cases of structures).

. The most important symbols are constants and theory inclusions (which are special cases of structures).

Constants

Constants are symbols that have a name and several optional components, namely

- a type (which is a term),

- a definition (which is also a term),

- a notation,

- zero or more roles and

- zero or more aliases.

Examples for constants include mathematical constants, functions, axioms, theorems and inference rules. Their concrete syntax is

The order of the object-level components is arbitrary. They are seperated by the object-delimiter  , the constant declaration itself is delimited by

, the constant declaration itself is delimited by  . Aliases are simply alternative names that can be used to refer to the constant and are useful e.g. in structures (see below).

. Aliases are simply alternative names that can be used to refer to the constant and are useful e.g. in structures (see below).

- If a constant has a declared type

t, then the termthas to be inhabitable (see ???). - If a constant has a definition but no declared type, its type is inferred from the definition.

- If a constant has both a type and a definition, the definition has to type-check against the given type, i.e. the judgment

|- <definition> : <type>has to hold. - Constants without either a type or a definition (assuming no additional type checking rules) are basically semantically void and thus uninteresting.

Notations

A notation is an arbitrary sequence of tokens, optionally followed by prec <precedence>.

- Tokens are either strings (representing the notation used in place of the constant name), integers (from 0 to 9) representing argument positions of the constant or special tokens of the form

%<argument><argument>. <precedence>is an arbitrary integer signifying the precedence (i.e. binding strength) of the notation.-

Of the special tokens there are presently the following varieties:

%I<integer>replaces an argument positionintegerand indicates that it is implicit;%R<string>replaces any string-token and indicates that the corresponding notation is right-associative (by default connectives are left associative).%D<string>escapes reserved symbols. E.g to obtain the notation%one uses the token%D%^ (Note that%R\<argument\>also escapesargument).

- There is also experimental support for flexary notation, for details see Issue #516.

This allows for almost arbitrary notation definitions.

Example: The notation for an infix operation

+could be given by# 1 + 2 prec 10. If a notation for a multiplication has a higher precedence (and thus a higher binding strength), e.g.# 1 ⋅ 2 prec 15, we can omit parentheses according to standard mathematical convention, so the expressiona + b ⋅ cwould be correctly parsed asa + (b ⋅ c).

Argument positions not given in a notation are assumed to be implicit, i.e. they have to be inferrable during type checking. This can be the case, if dependent type constructors are in scope, e.g. dependent products.

Example: A constant

cwith typetakes two arguments: an

a:Aand somex:F(a). Obviously, the second argument depends on the first, which allows MMT to infer the first argument from the second. Soccould have a notation# c 2omitting the first argument.

The %I<integer> token can be used to explicitly mark arguments as implicit. This may be necessary to disambiguate a notation whose last argument is to be left implicit.

Example: In natural deduction, the false elimination rule can be formalized as

⊦ false ⟶ {A:prop}⊦ Awith notation# falsE 1 %I2. The second argument of typepropcan be inferred by the type checker and therefore be left implicit. However, the notationfalsE 1would be ambiguous due to currying as to whether the return type is{A:prop}⊦ Aor⊦ A. As such the function could be called with one or two explicit arguments.%I2enforces the presence of an implicit argument of typepropin the context thereby disambiguating the notation and excluding the usage with two explicit arguments.

The %R<string> token can be used to make connectives right-associative. For example, implication is right-associative by convention. This can be handled by assigning it a notation 1 %R⇒ 2.

Roles

Roles serve as metadata-like annotations to constants. In most situations they are simply ignored. The following list of roles have some special meaning:

role Eqindicates that the constant represents an equality that can be used for rewriting.role Judgmentindicates that the constant is a Curry-Howard-style operator mapping propositions to types - as such, occurences of the symbol indicate theorems or axioms. Note that this role comes with a notation generator: for every functioninf_rulethat returns a⊦_, the notation generator generates a notation# inf_rule %I1 %I2 ...indicating that the prop-arguments in the dependent type operator{...}are left implicit. The autogenerated notation can be overwritten by manually declaring a notation. For more details look hererole Simplifyrequires the type of the constant to be of the form⊦ f(g(a)) ≐ b, where⊦has roleJudgmentand≐has roleEq. This induces a rewrite rule, that simplifies instances of the left side of the equation to the right side during type checking.

Metadata

Similar to how you can add meta data to modules, you can also annotate every declaration with arbitrarily many metadatums:

myAnnotationKey ❙

myAnnotationKey2 ❙

myAnnotationValue ❙

myAnnotationValue2❙

myConstant : someType ❘ meta ?myAnnotationKey ?myAnnotationValue

❘ meta ?myAnnotationKey2 ?myAnnotationValue2❙

Every metadatum declaration must

-

first specify a metadatum key, which is a reference to a symbol

Here, we give references to

myAnnotationKey(2), which we assume to be declared in the same theory here. As a formalizer, you might want to put that annotation key in some ambient meta theory. -

and second give an arbitrary metadatum value as a term.

Here, we keep it simple and just use a reference to yet another symbol as the term. If you use MMT/urtheories and import the strings theory thereof, you can also use strings, i.e.

meta ?myAnnotationKey "abc".

Note that you can have multiple metadatums on the same theory with the same key. In the implementation the metadatums form a list, hence this is allowed.

Imports/Inheritance between Theories

Large MMT theories are usually built modularly from smaller ones. The central declaration is that of an import between two theories. Similar to the ML module system, MMT supports unnamed imports, called includes and named imports, called structures.

Both make the contents of some theory <domain> available to the current one.

Structures may additionally modify the imported theory, most importantly by instantiating constants with concrete values in the importing theory.

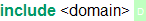

Includes

The syntax for a theory inclusion is

The include-relation between theories generates a partial order. In particular, includes are composed transitively, and including the same theory twice is redundant.

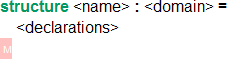

Structures

The syntax for structures is

, where <declarations> is a sequence of declarations.

- Even though structures are declarations, they have a module body and are thus delimited by the module delimiter

instead of the declaration delimiter

instead of the declaration delimiter  .

. - Simple includes are still delimited with

.

. - The name of each declaration in a structure has to correspond to the name of a declaration in the

<domain>. - Components (aliases, types, definitions etc.) explicitely given in a structure override the corresponding component of the declaration in the

<domain>, all other components are inherited from the latter. In particular, structures can introduce definitions for (not necessarily) previously undefined constants, in which case the (new) definition has to have the (induced/old) type of the constant. It is recommended to never override the type of a symbol in a structure. If no component of a declaration is to be modified, it can be left implicit. In this case a fresh copy of the declaration is inherited. If such multiplication is not desired for some declarations, they can be assigned to a previously inherited version of the declaration. - The full URI of an induced declaration

<declname>in a structure<struct>in a module<mod>is<mod> ? <struct> / <declname>. It is this declaration, that is visible from the outside and can be used in subsequent (to the structure) declarations. In contrast, the URI<mod> / <struct> ? <declname>refers to the plain declaration as declared directly in the structure, i.e. without inheritance. The latter should never be used outside of the API and is invisible to declarations outside of the structure. - Unlike simple includes, multiple named structures with the same

<domain>are not redundant. Each structure introduces fresh (possibly modified) copies of the declarations in the domain. - The limit of the previous point is the meta theory of the domain. If two structures

s1,s2have corresponding domainsdom1,dom2with the same meta theorymeta, then everything in the dependency closure ofmetawill be included exactly once.

Implementation note: Because includes and structures are often treated exactly the same way, the MMT system represents an include as a structure with empty body and the induced name [<domain>]. API-wise this corresponds to having an MPath referencing a module (e.g. a theory) and then taking a ComplexStep to refer to the inclusion: MPath ? ComplexStep(MPath).

Example

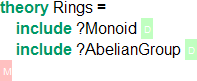

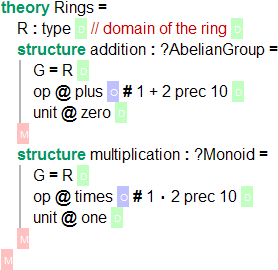

Let us assume, we have a theory Monoid with a constant G for the domain of a monoid, op for the monoid operation, unit for the unit of the monoid and the usual axioms. The latter might be included in (and extended by) a theory AbelianGroup adding the additional axioms. then we can use structures to form a theory Ring, using the theory Monoid for multiplication and AbelianGroup for addition. If we use includes, like this

the (transitively twice) included instances of Monoid will be identified, defeating the purpose. As mentioned above, named structures prevent that, and allow us to additionally

- identify the two instances of the domain

G, - give new aliases to the instances of

op(e.g.plusandtimes) and ofunit(e.g.zeroandone) and - give the instances of

opnew desired notations.

Thus, the correct theory Ring could look like this:

All the monoid/group axioms are imported via the structures and are thus available for the respective new symbols. If Monoid and AbelianGroup have the same meta theory (e.g. first_order_logic), then all symbols imported via that (e.g. quantifiers, logical connectives etc.) are identified across the two structures.

Derived Declarations

Derived declarations are declarations, which are not interpreted directly but elaborated into external declarations by a structural feature. Their syntax and semantics is defined by the corresponding structural feature.

Rules

Rules are special Scala objects that can be declared in an MMT theory Thy to change the semantics of Thy-terms. For example,

- all typing rules for the toplevel meta-theory

- lexing rules for user-defined literals

are provided as rules.

Users typically do not need to use rules except when designing their own type systems outside logical frameworks.

To declare a rule, just write rule PATH inside Thy, where PATH is the MMT URI of a Scala object on the current class path - MMT will dynamically load the Scala object and use it in all Thy-algorithms.