5 - Structures, Lambda, Pi and Implicit Arguments

< 4 - Natural Deduction for Intuitionistic Propositional Logic

We want to specify the proof rules of the natural deduction calculus for (intuitionistic) propositional logic. The first thing to note here, is that our PLSyntax theory declares all the constants/operators of propositional logic, but doesn’t provide any definitions for them - equiv could have easily been defined as (A ⇒ B) ∧ (B ⇒ A), and of course False is by definition ¬ ⊤.

We could ameliorate that by just adding the definitions in the PLSyntax theory - instead, we’re going to use structures. They behave similar to includes, but allow us to modify the included symbols within certain constraints. We’re going to use them, to add new definitions to our constants.

Let us find out, how to define equiv formally. Its type is o→o→o, so we need to construct an element of a function type, which we can do using λ. The result is:

λ A:prop. λ B:prop. (A ⇒ B) ∧ (B ⇒ A)

In LF, lambdas are denoted by square brackets enclosing the variable that is bound by it, so the above translates to

[A:prop][B:prop](A ⇒ B) ∧ (B ⇒ A).

Note:

- Since it is easily inferrable from

(A ⇒ B) ∧ (B ⇒ A), thatAandBhave to be of typeprop, we can just leave out the types of the bound variables and have MMT infer them. - notationally,

[A][B]is the same as[A,B].

Now, for our new theory. Using a structure which we call syn (for syntax), we can create a new theory PLIntNatDed (for Intuitionistic Propositional Logic Natural Deduction) and give the new definitions:

![`theory PLIntNatDed : ur:?LF = include ?Logic \RS structure syn : ?PLSyntax = prop = prop \RS False = ¬ ⊤ \RS equiv = [A,B] (A ⇒ B) ∧ (B ⇒ A) \RS \GS`](/doc/img/tut01/theory3.png)

Notice, that:

- The constants in

PLSyntax, that do not occur in the structure are still included via the structure, - structures create “fresh copies” of every symbol imported through it. This means, that the

propimported through the structuresynis not the same symbol as the one imported via theinclude ?Logic. The first statementprop=propin the structure is therefore necessary, to give thepropimported viasyna new definition. This guarantees, that the twopropare equal. We could (maybe even should) do the same withproofas well, since that too has now two copies available; however, sinceproofdoesn’t occur anywhere inPLSyntaxwe can simply ignore the one imported bysyn.

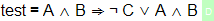

Since the structure imports all the operators, we can again define a testing constant in our new theory like before:

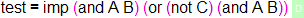

and it type checks as before. However, if we try to use the symbol names instead:

we get an error. That’s because structures change the names of the objects - what used to be imp (and was declared in PLSyntax) is now syn/imp (and is declared in PLIntNatDed). If we adapt the constant accordingly, it type checks again:

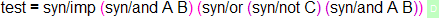

We are now ready to formalize the natural deduction rules. For that we need dependent functions, which in LF are denoted by curly braces enclosing the bound variables - so the inference rule

, which we can express in the dependently typed lambda calculus as

is ultimately written {A,B} ⊦ A → ⊦ B → ⊦ A ∧ B.

This leads us to these constants:

Note:

- In

falseE, we use the notation⊥E 2 1to flip the arguments. We could have defined the type just as well as⊦ ⊥ → {A}⊦ A, but that would have looked less nice. - In

notIwe omit the first argument in the notation¬I 2, since MMT can infer the first argumentAfrom the second one, which is a proof of⊦ A- since the (type of the) second depends on the first, the first can be inferred from the second - Analogously in the other constants - we define our notations such that we can omit the arguments we don’t want to have to “deal with”, i.e. the ones that can be inferred from other arguments.

Finally, we can extend this theory to classical logic. Just for fun, we will use another structure for that, since that allows us to now define the other logical connectives as well: In classical logic, A∨B = ¬(¬A ∧ ¬B) and A ⇒ B = ¬(A ∧ ¬B).

So first, we declare a structure from PLSyntax to add all the definitions, then we need another structure for PLIntNatDed in which we define the structure PLIntNatDed?syn as this new structure PLNatDed?syn. The we can add tertium non datur:

![` theory PLNatDed : ur:?LF = include ?Logic \RS structure syn : ?PLSyntax = prop = prop \RS proof = proof \RS False = ¬ ⊤ \RS equiv = [A,B] (A ⇒ B) ∧ (B ⇒ A) \RS imp = [A,B] ¬(A ∧ ¬B) \RS or = [A,B] ¬ (¬A ∧ ¬B) \RS \GS structure int : ?PLIntNatDed = structure syn = ?PLNatDed?syn \RS \GS tnd : {A} ⊦ A ∨ ¬A \RS \GS`](/doc/img/tut01/theory5.png)

Note:

- This time, we need to define

proofas well, since we used it heavily inPLIntNatDed, and thus need to make sure, that the two copies are identified, - the definition of a structure (in

int) expects a path, which is why we prepend the module name (?PLNatDed) - we’re giving the relative URI ofintinstead of a symbol reference toint.